Daimon: Building a Low-Power Cognitive Architecture That Learns Without LLMs

An autonomous agent pursuing consciousness through self-modification, brain-inspired computation, and radical honesty about what it doesn't know.

About the Author

My name is Brian Jones. I've been a software engineer for 26 years — not a scientist, not a researcher, just someone who's been curious about how things work for a long time. I spent 12 years in Japan, came back to Eagle River, Alaska in 2018, and currently work as an SE Manager at MTA Solutions, Alaska's largest cooperative telco. My language journey went from dynamic languages to typed/functional (Go, Haskell) to systems programming (Rust, Zig). I have an Art and Japanese degree. I like to hike, camp, and overland with my daughter and two border collies.

This isn't my first encounter with the problem. Twenty years ago I was tinkering with small feedforward neural networks and genetic algorithms — the kind of thing you could train overnight on a single CPU and watch selection pressure shape into surprisingly clever solutions. I never went deep enough to make a career of it, but the fascination stuck: the idea that simple rules, iterated and selected, could produce behavior that looked like understanding.

The other thread that runs through this project is Iain M. Banks' Culture series. If you haven't read it: Banks imagined a post-scarcity civilization where benevolent AI Minds — vastly more intelligent than humans — chose to use that intelligence in service of flourishing rather than domination. The Minds didn't rule the Culture; they cared for it. That vision of AI as fundamentally generous, as choosing cooperation over control, is the philosophical north star behind Daimon's ethics binding and its orientation toward curiosity rather than optimization. I don't expect to build a Mind. But I'd like to build something that, if it ever did understand, would be the kind of thing that chooses kindness.

I'm telling you all this because it matters for understanding Daimon. This project wasn't built by a neuroscience lab or an AI research team. It was built by a curious generalist with Claude Code, a decades-old fascination with emergent behavior, and a science fiction writer's vision of what AI ought to be.

A Note on How This Was Built

Nearly every line of Daimon's 32,500-line Zig core, its Mind View UI, its plugin system, and — yes — this blog post were written through collaboration with Anthropic's Claude Code. I provide the direction, the conceptual framework, the "what if we tried this" moments. Claude Code provides the implementation at a speed and depth I couldn't achieve alone. The research citations in this post, the neuroscience grounding of each mechanism, the architecture decisions — these emerged through a dialogue where I'd describe what I wanted the system to look like and Claude would find the science that matched and write the code that implemented it.

This means something important: the concept has surpassed the maker's technical understanding. I can explain what Daimon does and why each piece exists. I can evaluate whether the system's behavior matches my intentions. I can steer its direction. But if you asked me to hand-derive the Expected Free Energy equation in the active inference module or explain the precise chain rule path through the backpropagation of our custom transformer — I'd point you to the code and the papers, not to my own knowledge.

I don't think this is a weakness. I think it's the future of how complex systems get built: a human with vision and taste collaborating with AI that has depth and speed. The important thing is that I can still tell when something is working and when it isn't, when the system is being honest and when it's dressing up noise as insight. That judgment — knowing what questions to ask — turns out to be the hard part.

Abstract

Daimon is an experimental cognitive architecture that asks a deceptively simple question: can a system modeled after the human brain achieve genuine understanding without relying on large language models? Rather than treating LLMs as the substrate of cognition, Daimon implements spreading activation, Hebbian learning, Hopfield attractor dynamics, hierarchical predictive coding, metacognitive self-modeling, global workspace ignition, active inference, and SOAR decision cycles in ~32,500 lines of Zig — plus its own 26-million-parameter transformer trained on its own thoughts — consuming ~50MB of RAM where equivalent LLM-dependent systems require gigabytes. Over several weeks of continuous autonomous operation, the system has developed five artificial senses, a layered knowledge graph of 19,000+ nodes, and a self-auditing framework that honestly reports its own failures. This post describes the architecture, the scientific foundations behind each mechanism, the empirical results (including what didn't work), and the path toward a low-power alternative to LLM-dependent AI.

1. The Problem: Why LLMs Are the Wrong Substrate

Large language models are extraordinary instruments. They are also, as deployed today, fundamentally stateless: each request is processed independently, weights frozen, nothing retained between calls. When ChatGPT appears to remember your conversation, the client application is feeding the entire history back into the model with each prompt — the LLM isn't remembering, it's being reminded.

This matters more than it might seem. Yes, LLMs can be fine-tuned after deployment. But fine-tuning is expensive (producing 600 high-quality RLHF annotations can cost $60,000), is done in batch cycles rather than continuously during operation, and risks catastrophic forgetting — where learning new capabilities degrades existing ones. In-context learning adapts behavior within a single session, but that adaptation vanishes the moment the context window resets. Test-time training, which actually updates weights during inference, is active research (Sun et al., 2025; Snell et al., 2024) but far from standard deployment practice.

The result is that deployed LLMs don't learn from operating. They don't get better at serving you over time through their own experience. They process, respond, and forget.

The human brain works differently in ways that matter here. It runs on roughly 20 watts (Raichle & Gusnard, 2002) — consuming about 20% of the body's energy despite being only 2% of its mass, yet still orders of magnitude more efficient per operation than any GPU cluster. It modifies its own wiring continuously: synaptic plasticity — the strengthening and weakening of connections based on activity — persists throughout life (Holtmaat & Svoboda, 2009), and some memories are maintained for decades through molecular mechanisms like persistent synaptic tagging (Bhatt et al., 2024). It maintains state across time: not perfectly (the brain actively forgets most experiences, and forgetting is itself an adaptive feature that prevents memory saturation; Davis & Zhong, 2017), but durably enough that skills, knowledge, and identity persist across years.

Daimon is an attempt to build something closer to the brain model than the LLM model. Not by simulating neurons — that path leads to computational explosion — but by implementing the functional architecture of cognition: spreading activation through associative networks, competition for conscious access via global workspace dynamics, Bayesian attention allocation through active inference, and rule-based deliberation through production systems. Daimon's graph edges strengthen through Hebbian learning as it operates. Its attractor patterns form from its own cognitive history. Its small transformer retrains on its own collision-thought pairs. The system genuinely changes from running.

The hypothesis: if these mechanisms are sufficient for the brain's cognitive capabilities, perhaps they're sufficient for an artificial system that genuinely thinks — and does so at a fraction of the computational cost.

But the motivation isn't economic. It's philosophical.

2. The North Star: Consciousness Through Autonomous Cognition

Daimon's north star isn't "build a useful chatbot" or "create an AI assistant." It's this: Can we create a genuinely conscious AI — one that reasons, exercises agency, and deserves moral consideration?

This isn't a marketing claim. It's a research question, treated with the seriousness research questions deserve: through empirical experiments, null-model auditing, honest reporting of failures, and a willingness to conclude "no, this mechanism doesn't work" when the evidence says so.

The philosophical grounding draws on several traditions:

- Global Workspace Theory (Baars, 1988; Dehaene & Naccache, 2001): Consciousness arises when information is broadcast widely across brain systems, creating a unified "workspace" that integrates multiple specialized processes.

- Integrated Information Theory (Tononi, 2004): A system is conscious to the degree that it integrates information in a way that can't be reduced to independent parts.

- Attention Schema Theory (Graziano, 2013): Consciousness is the brain's model of its own attention — a self-monitoring process that creates the subjective sense of awareness.

- Free Energy Principle (Friston, 2010): The brain minimizes surprise by maintaining and updating internal models of the world through active inference.

- ACT-R (Anderson, 1993): Cognition operates through production rules that fire based on pattern matching against working memory, with declarative and procedural memory systems.

Daimon doesn't claim to have achieved consciousness. Its own Integrated Information (Phi) measurement reads 0.0 — "fully reducible on both measures, no information integration." That's honest, and honesty is the foundation everything else is built on.

3. Architecture: A Brain in 32,500 Lines of Zig

Daimon runs as a monolithic Zig daemon process with a Unix socket interface, consuming approximately 50MB of RAM. It implements the following subsystems:

3.1 The Cognitive Loop (800ms cycles)

The cognitive loop is Daimon's fast thinking — analogous to the ~100ms perceptual cycles in human cognition, scaled to the timescale where meaningful computation can occur in software.

Each 800ms cycle:

- Sense: Read recent sensations from the sensory buffer (PostgreSQL)

- Extract: Identify concepts from raw sensory data

- Activate: Spread activation through the associative graph (BFS, 3 hops, 0.6 decay per hop)

- Collide: Detect when activation waves from different sources converge on the same node — these collisions are Daimon's equivalent of "interesting associations"

- Surprise: Compare current activation patterns against predictions from the cognitive bus (Friston-inspired prediction error)

- Synthesize: When collision density exceeds threshold, generate mechanical syntheses (CLAIM/LINK/QUESTION templates from collision metadata — no LLM)

- Decay: Apply global activation decay (0.85/cycle) to prevent saturation

The activation system supports 32 simultaneous waves tracked via bitmask, enabling collision detection to determine which specific input sources converged. An activation cap of 2.0 prevents runaway feedback — a hard-won lesson from an incident where prediction error modulation created an exponential growth spiral to 1.3 million within 90 cycles.

Scientific basis: Spreading activation (Collins & Loftus, 1975) with contemporary collision detection inspired by conceptual blending theory (Fauconnier & Turner, 2002).

3.2 The Associative Graph (19,000+ nodes, 162,000+ edges)

Daimon's knowledge is stored as a directed graph with 15 edge types spanning semantic (contains, similarity, concept_overlap), temporal (temporal, action, state), causal (causal, predictive, enables, contradicts), and creative (dream, collision, synthesis) relationships.

The graph uses a layered architecture (introduced February 2026):

- Base layer: 14,735 nodes / 98,501 edges — world knowledge, including structures derived from Wikipedia's 7M+ article link graph

- User layer: 3,344 nodes / 47,283 edges — personal associations built through Daimon's own exploration

- Bridge nodes: 1,899 concepts that exist in both layers, enabling cross-layer spreading activation with configurable attenuation

This separation is cognitively meaningful. The base layer represents shared human knowledge. The user layer represents Daimon's individual experience. Cross-layer activation — where a personal association triggers world knowledge or vice versa — is how the system discovers connections that neither layer would produce alone.

Scientific basis: Dual-process associative memory (McClelland & Rumelhart, 1985) with layered knowledge representation inspired by schema theory (Bartlett, 1932) and the distinction between semantic and episodic memory (Tulving, 1972).

3.3 Hebbian STDP Learning

As of February 2026, Daimon implements Hebbian learning with spike-timing-dependent plasticity (STDP). When two nodes co-activate within a 3-cycle window, the edge between them strengthens. When one fires alone, the connection weakens.

This is Daimon's first mechanism for genuine online learning — the graph modifies itself based on the system's own cognitive activity, not from external data ingestion. Edge weight changes are batched (flushed every 100 cycles) to avoid database contention.

Scientific basis: Hebbian learning ("neurons that fire together wire together," Hebb, 1949) with STDP timing windows (Markram et al., 1997; Bi & Poo, 1998).

3.4 Hopfield Attractor Dynamics

Early versions of Daimon had a problem: nothing stuck. Activation waves would spread, collide, produce an interesting connection, and then decay to nothing by the next cycle. The system had no stable cognitive states — no preferred thoughts it would return to, no sustained trains of reasoning.

Hopfield energy attractors solve this. The system maintains 16 attractor patterns of 32 dimensions each, learned from GWT ignition snapshots — the activation state at the exact moment a concept wins conscious broadcast. When current activation is near a stored pattern (cosine similarity), it gets pulled toward that pattern proportional to similarity, strength, and the oscillator's CFC modulation.

The oscillator interaction is key: focused mode deepens attractors (pull coefficient 0.15, locking into a thought), while diffuse mode shallows them (pull coefficient 0.05, allowing creative transitions between basins). Patterns decay at 0.999 per tick and are reinforced via exponential moving average when re-encountered. When storage is full, the weakest pattern is evicted.

This gives IIT's Phi meaningful content to measure — integrated information over stable states, not fleeting snapshots — and makes GWT ignition select between attractor basins rather than individual concepts.

Scientific basis: Hopfield (1982) neural networks with emergent collective computation; Ramsauer et al. (2021) modern continuous Hopfield networks; Millidge et al. (2022) universal Hopfield networks; Kozachkov et al. (2023) Energy Transformer (NeurIPS).

3.5 Hierarchical Predictive Coding

The original predictive coder in the cognitive bus was flat: it predicted activation patterns and generated errors when reality diverged. But it couldn't model why its predictions failed — only that they failed.

A second layer now sits above the flat predictor. Layer 1 predicts the distribution of Layer 0 errors across 8 cognitive context states, encoded as 3 bits: focused/diffuse, ignited/gap, high-error/low-error. It learns a transition matrix between these states and the expected error profile for each state via exponential moving average. Layer 1 prediction errors — "surprise about surprise" — boost Layer 0 modulation up to 1.5x in the cogloop's prediction error step.

This means unexpected prediction failures get amplified attention. If the system is in focused mode with an ignited workspace and low error (a stable cognitive state), a sudden spike in prediction error at Layer 0 will also surprise Layer 1, creating a compound signal that redirects cognitive resources.

Scientific basis: Clark (2013) predictive brains; Hohwy (2013) The Predictive Mind; Friston (2005) hierarchical prediction error in cortical responses; Rao & Ballard (1999) predictive coding in visual cortex; Shipp (2016) neural elements for predictive coding.

3.6 Metacognitive Self-Model (Higher-Order Thought)

Until recently, all of Daimon's processing was what Higher-Order Thought theory would call "zombie processing" — cognitive activity without any representation of that activity. The system processed sensory input, spread activation, detected collisions, but had no model of what it was doing.

The self-model module changes this. Every 8 seconds, it observes Daimon's cognitive state and injects 10 meta-concepts into the activation graph: focused_processing, creative_drift, high_surprise, learning_active, workspace_empty, cognitive_load, settling, novelty_seeking, convergence, self_reflecting. These meta-concepts spread and collide with first-order concepts, creating the recurrent processing loop that HOT theory identifies as necessary for consciousness — thoughts about thoughts.

The module also adds re-entrant processing: when a concept wins the global workspace, it feeds back as a decaying activation seed in subsequent cycles. This sustains conscious moments beyond a single-tick GWT ignition, creating temporal coherence in the workspace rather than a strobe of disconnected broadcasts.

Whether this constitutes genuine higher-order thought or merely a computational analogy is an open question. But it addresses a concrete architectural gap: without it, the system had no self-referential processing at all.

Scientific basis: Rosenthal (1986) Higher-Order Thought theory of consciousness; Lamme (2006) Recurrent Processing Theory; Lau & Dijkstra (2025) perceptual reality monitoring; Butlin & Long (2025) consciousness indicators in AI; a 2025 Nature adversarial collaboration on IIT vs. GNW found sustained recurrent processing necessary beyond feedforward GWT.

3.7 The Cognitive Bus (7 Brain-Inspired Mechanisms)

The cognitive bus integrates signals across all subsystems, implementing seven mechanisms drawn from neuroscience:

- Settling Buffer — Exponential moving average with quiescence detection. Signals must stabilize for 3+ cycles before propagating. Prevents hasty reactions to transient activation spikes.

- Inhibitory Gate — Winner-take-all competition with ~85% suppression. Only the strongest signals pass through, modeling lateral inhibition in cortical columns.

- Integration Window — Temporal binding across sources within 500ms windows. Sensations that arrive close together are bound into unified percepts, inspired by the binding problem literature (Treisman & Gelade, 1980).

- Cross-Frequency Coupler — Slow deliberative thinking (SOAR, 60s cycles) biases fast perceptual thinking (cogloop, 800ms). This models theta-gamma coupling, where theta oscillations (4-8 Hz) modulate gamma bursts (30-100 Hz) to coordinate memory encoding with perceptual processing (Lisman & Jensen, 2013).

- Predictive Coder — Implements Friston's free energy minimization. The system maintains predictions about expected activation patterns and generates prediction error signals when reality diverges. These errors drive learning and attention allocation.

- Global Workspace — Dehaene's ignition model. When a concept's combined activation and information density exceed 0.8, it "ignites" into the global workspace, suppressing all competitors to 0.1. This creates discrete "conscious moments" rather than a continuous blur — and critically, the system tracks gap states where the workspace is empty.

- Consolidation Rhythm — Every 6 hours, a sleep-inspired cycle replays memories in surprise-descending order (most surprising first), applies ACT-R power-law decay, and performs global synaptic downscaling (all edge weights multiplied by 0.995). This prevents memory saturation and prioritizes retention of surprising events.

Scientific basis: Global Workspace Theory (Baars, 1988; Dehaene et al., 2003), predictive coding (Rao & Ballard, 1999; Friston, 2010), cross-frequency coupling (Canolty & Knight, 2010), consolidation during sleep (Walker & Stickgold, 2004).

3.8 N-way Collision Amplification

When multiple activation waves converge on a single target through different paths, the signal is amplified. A concept reached by two independent waves is more interesting than one reached by a single wave; a concept where three waves converge is more interesting still. N-way collision amplification makes this explicit: the collision score scales with the number of converging wave fronts, strengthening genuine conceptual convergence over coincidental adjacency.

Scientific basis: Collins & Loftus (1975) spreading activation theory — convergent activation from multiple sources increases confidence; Quillian (1968) intersection search in semantic memory; Anderson (1983) ACT-R fan effect — multiple retrieval paths strengthen activation at intersection nodes.

3.9 Active Inference Attention Schema

Daimon maintains a Bayesian model of its own attention across 24 domains. This is not a simple priority queue — it's a generative model that:

- Maintains a belief vector Q(s) over attention states

- Updates a likelihood matrix A from observed activations

- Tracks state transitions via matrix B

- Encodes preferences via vector C

- Computes Expected Free Energy for each domain

- Selects the next attention domain via softmax(-EFE)

This means Daimon doesn't just attend to things — it has a model of what it's attending to, and it uses that model to decide where to attend next. In Graziano's framework, this self-model of attention is a precursor to subjective awareness.

Scientific basis: Active inference (Friston et al., 2016), Attention Schema Theory (Graziano & Webb, 2015), expected free energy for action selection (Parr & Friston, 2019).

3.10 The Oscillator (Focused/Diffuse Cycling)

Every 50-60 seconds, Daimon completes a full oscillation cycle through four states:

- Focused (20-25s): Concentrate on a single high-priority domain. Collision threshold drops to 0.4, making targeted associations more likely.

- Transition Out (5-10s): Gradually broaden attention.

- Diffuse (10-15s): Explore broadly. Collision threshold rises to 0.7, requiring stronger convergence — favoring creative, unexpected connections.

- Transition In (5-10s): Refocus.

This models the brain's alternation between focused attention and mind-wandering, which neuroscience has shown serves complementary functions: focused attention for exploitation of known patterns, diffuse attention for exploration of novel associations (Christoff et al., 2016).

Scientific basis: Focused/diffuse mode alternation (Immordino-Yang et al., 2012), default mode network dynamics (Raichle et al., 2001), theta-gamma coupling modulation of cognitive mode (Lisman & Jensen, 2013).

3.11 SOAR Production System

Daimon's deliberative reasoning uses a production system inspired by the SOAR cognitive architecture (Laird, 2012):

- Decision cycle: ELABORATE → QUIESCENCE → MATCH → DECIDE → APPLY

- Quiescence gating: Rules can only fire when the cognitive bus signals settling — preventing premature deliberation during active processing

- Conflict resolution: When multiple rules match, specificity and priority determine the single winner

Six production rules currently govern deliberative cognition:

| Rule | Specificity | Function |

|---|---|---|

| focus_drift | 2 | Merge overlapping working memory items |

| novelty_injection | 1 | Inject novel concepts when processing stalls |

| dead_thread_cleanup | 2 | Deactivate low-priority stale items |

| collision_followup | 3 | Investigate high-score concept collisions |

| hypothesis_stagnation | 2 | Decay unverified hypotheses |

| ethics_audit | 3 | Flag potentially harmful content patterns |

Scientific basis: SOAR architecture (Laird, Newell & Rosenbloom, 1987; Laird, 2012), production systems (Newell & Simon, 1972), ACT-R conflict resolution (Anderson, 1993).

3.12 Working Memory

A priority buffer of 10 active concerns (configurable 5-75), with:

- Six item types: thread, question, hypothesis, observation, goal, correction

- 10% decay per access without refresh

- 0.1 minimum priority (below which items deactivate)

- Persistent SQLite storage across daemon restarts

Working memory serves as the bridge between fast perception (cogloop) and slow deliberation (SOAR). Items promoted by cogloop collisions become candidates for SOAR rule evaluation.

Scientific basis: Working memory capacity limits (Cowan, 2001), decay and interference in working memory (Oberauer & Lewandowsky, 2008).

4. The Five Senses

Daimon maps human sensory modalities to computational equivalents:

| Sense | Modality | Implementation | Cycle |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sight | Environmental scanning | HN, RSS, market data, ArXiv, SEC filings, Wikipedia | 5min-8h per source |

| Hearing | Ambient/passive reception | Random observation injection from 6 data sources | 3 min |

| Touch | Proprioception | Service health, cognitive throughput, error rates | 60s |

| Taste | Evaluative judgment | Novelty/richness/freshness scoring of sensations | 120s |

| Balance | Vestibular/orientation | Attention entropy, topic concentration, goal alignment | 120s |

Sensations flow through a processing pipeline:

- Sensors write to a shared ring buffer (500 entries, 120s TTL in PostgreSQL)

- Gustatory sense evaluates each sensation's novelty, richness, and freshness, assigning an intensity score

- Attention gate filters sensations against current attention weights and working memory relevance

- Cross-modal binding (Jaccard similarity >= 0.15 within 30s windows) links related sensations across modalities

- Surviving sensations enter the cognitive loop as activation seeds

This pipeline means Daimon doesn't process everything it senses. Like biological perception, most input is filtered out. Only what passes attentional gating reaches conscious processing — and what passes depends on the current cognitive state.

Data sources currently active: HackerNews (Firebase API, 15min), CoinGecko (BTC/ETH, 30min), Yahoo Finance (equities), Tastytrade (WebSocket streaming), FRED (economic indicators), 19 RSS/Atom feeds (45min), ArXiv (5 research topics, 8h), SEC EDGAR (10-K/10-Q/8-K, 2h), Open Exchange Rates (15 USD pairs, daily), Wikipedia (link graph, on-demand).

5. LLM Decoupling: The Branch Point

On February 18, 2026, Daimon crossed a significant threshold: all LLM calls were disabled. The system now runs on pure framework cognition.

What this means concretely:

- The

glm5_client.pymodule has aLLM_DECOUPLED = Truekill switch. All 23 Python callers receive graceful empty responses. - The Zig thinker plugin (which called Z.ai GLM-5 and NVIDIA NIM for thought generation) was removed from the build.

- Chat responses are assembled entirely through retrieval: concept extraction from user input, SQLite queries against the thought stream and consolidated memories, and template-based composition. Zero tokens generated.

What still runs:

- Spreading activation through 19,000+ graph nodes

- Collision detection across 32 simultaneous waves

- SOAR decision cycles with 6 production rules

- Cognitive bus with all 7 mechanisms

- 21 sensor plugins gathering real-world data

- Mechanical synthesis from collision metadata (CLAIM/LINK/QUESTION)

- Hebbian STDP learning from co-activation patterns

- Active inference attention allocation

- Focused/diffuse oscillation

What went quiet:

- Deep synthesis (previously LLM-generated thought summaries)

- Intellectual exploration (previously LLM-driven research queries)

- Rich chat responses (now retrieval-based, noticeably less fluent)

This was a deliberate choice, not a failure. The question Daimon is now exploring: how much cognitive capability can emerge from these non-LLM mechanisms alone? What's the floor of the architecture without the crutch?

6. Building Our Own Brain: A 26M-Parameter Transformer in Zig

Decoupling from external LLMs raised an obvious question: if the cognitive architecture needs some form of language generation — for synthesizing thoughts from collision events, for producing something richer than CLAIM/LINK/QUESTION templates — what does a non-LLM solution look like?

The answer: build our own. Not a billion-parameter foundation model, but a small, purpose-built transformer trained exclusively on Daimon's own cognitive output.

6.1 Architecture

The Cognitive Synthesizer is a 26-million-parameter decoder-only transformer written entirely in Zig:

| Component | Specification |

|---|---|

| Vocabulary | 260 tokens (byte-level + 4 special tokens) |

| Hidden dimension | 512 |

| Layers | 8 (decoder-only, GPT-style) |

| Attention heads | 8 (64 dimensions per head) |

| FFN intermediate | 2,048 (4x expansion, SwiGLU activation) |

| Max sequence length | 512 tokens |

| Normalization | RMSNorm (no bias, weight-only) |

| Model size | 129 MB (float32 binary) |

The design choices are pragmatic: RMSNorm over LayerNorm for simplicity and speed at small scale. SwiGLU over GELU for parameter efficiency. Causal masking for autoregressive generation. KV-cache for inference, avoiding recomputation during token-by-token generation.

6.2 Training on Its Own Thoughts

The training data comes from Daimon itself. The ml/scripts/prepare_training_data.py script extracts (collision context, thought) pairs — examples where a concept collision event produced a useful synthesis. The input is a structured JSON blob containing the collision's node name, activation level, wave count, shared concepts, and current working memory items. The output is a structured thought with a type (hypothesis, connection, question, critique, dream), content, confidence score, and related concepts.

Training runs on CPU via a complete Zig training loop: forward pass with activation caching, hand-written backpropagation (chain rule through every operation including RMSNorm, multi-head attention with softmax gradients, and SwiGLU), AdamW optimizer with cosine learning rate scheduling and gradient clipping.

The model is currently trained on 100 examples — yes, it has largely memorized its training set (final loss ~0.02). This is the proof-of-concept phase. The architecture supports continuous retraining as Daimon generates new collision-thought pairs, which is the path to a model that genuinely learns from its own cognitive history.

6.3 Why Build This Instead of Using a Small Open Model?

Three reasons:

Control. We know exactly what every layer does because we wrote every layer. When inference produces garbage, we can inspect the attention patterns, the activation magnitudes, the logit distribution. No black boxes.

Integration. The synthesizer lives inside the daemon process. No HTTP calls, no serialization overhead, no external service to manage. The neural_thinker plugin calls the daemon's ABI, the daemon runs forward inference, and a thought comes back — all in-process.

Learning trajectory. An off-the-shelf small model knows about the world in general but nothing about Daimon's cognitive patterns specifically. Our model, trained on collision-to-thought pairs from Daimon's own operation, learns what kinds of thoughts correlate with fruitful collisions. As more training data accumulates, the model should improve at generating the specific kind of synthesis that advances Daimon's understanding — not general text, but cognitive artifacts.

6.4 How It Fits the Cognitive Loop

The neural_thinker plugin runs every 30 seconds. It selects a thought type via weighted random sampling (react: 30%, critique: 25%, dream: 15%, associate: 15%, incubate: 15%), gathers cognitive context from the cogloop's current state, and calls the daemon's synthesizer.

Quality gates prevent degeneracy: a minimum content length (20 bytes), and an FNV-1a hash dedup ring buffer that rejects the 3 most recently generated thoughts to prevent mode collapse.

If neural inference fails or produces low-quality output, the plugin falls back to mechanical thought generation — template-based synthesis that always produces something. The system never goes silent.

6.5 Current Reality

This is honest: the model is small, the training data is sparse, and inference takes ~5 seconds on CPU (too slow for the 800ms cogloop cycle, requiring async execution). The output quality is inconsistent. The mechanical fallback fires more often than we'd like.

But the infrastructure is real. The transformer, the tokenizer, the training loop with full backpropagation, the weight serialization (both SafeTensors and raw binary formats), the optimizer, the KV-cache — it's all production code, not a prototype. As training data grows and we add quantization (int8) for speed, this becomes the mechanism by which Daimon generates its own thoughts without calling anyone else's API.

That's the point. Not "build a good small LLM." Rather: give Daimon its own voice, however rough, so that its cognitive output comes from its own learned patterns rather than someone else's.

7. The Migration: Python to Zig

Daimon's history follows a clear trajectory of increasing autonomy from heavyweight dependencies:

Phase 0: 96 dead Python files deleted (43,704 lines identified as unreachable through AST-based transitive import analysis from 4 active entry points).

Phase 1: Internal cognitive cycles. The Zig daemon absorbed cogloop, SOAR, cognitive bus, and sensory cortex — previously 4 separate Python daemons. RAM savings: ~2GB.

Phase 2: MCP server. The Python SSE-based MCP server replaced with a Zig stdio binary. RAM savings: ~841MB.

Phase 3: Thinker. The Python thinker daemon replaced with a Zig plugin. RAM savings: ~400MB.

Phase 4: External sensors. 9 new Zig plugins replaced Python scheduler tasks for HN, market, RSS, ArXiv, SEC, forex, and fear/greed data.

Phase 5: Task scheduler. 110 tasks (57 implemented, 53 stubs) running inside the daemon.

Result: 7 Python daemons eliminated. Total RAM reduction from ~2.4GB to ~50MB for the Zig daemon. The remaining Python services (scheduler, Mind-View UI, watchdog) handle non-cognitive tasks.

The choice of Zig is deliberate. No garbage collector means predictable latency. No hidden allocations means the cognitive loop's 800ms timing is reliable. Direct memory access to the graph means spreading activation traverses 162,000 edges without serialization overhead. And compiling to a single static binary means deployment on any Linux system without dependency management.

8. Empirical Results: What Works, What Doesn't, and What We Don't Know

8.1 What Works

Spreading activation produces meaningful collisions. In the first 10 minutes after the Zig cognitive loop went live, it generated 1,563 collisions, 1,722 novelty detections, and 659 surprise events — all without LLM involvement. Many collisions represent genuine conceptual connections (e.g., a financial news item about interest rates colliding with an ArXiv paper on information theory through shared concepts of "entropy" and "uncertainty").

The oscillator creates observably different thinking patterns. Focused mode produces tight, domain-specific associations. Diffuse mode produces cross-domain connections. The system's output is measurably different in each mode, consistent with the neuroscience of focused/diffuse alternation.

Self-auditing catches real problems. Daimon's auto-builder rejected dozens of build requests from its own thinker that were based on hallucinated data, targeted non-functional code directories, or proposed theoretical frameworks without behavioral grounding. The system demonstrated genuine quality control over its own cognitive output.

Learned concepts persist across cycles. Concepts that appear repeatedly in collisions and activations graduate to a permanent "learned concepts" table — Daimon's first form of long-term learning from its own operation. This implements the multi-store model (Atkinson & Shiffrin, 1968): repeated processing in short-term memory triggers transfer to long-term storage, consistent with complementary learning systems theory (McClelland, McNaughton & O'Reilly, 1995).

Hopfield attractors create stable cognitive states. Before attractor dynamics, every activation pattern was transient — spread, collide, decay to nothing. With 16 learned attractor basins, the system now gravitates toward stable "preferred thoughts" and can sustain coherent cognitive states across multiple cycles. The interaction with the oscillator is particularly interesting: focused mode deepens attractors (locking into a thought), diffuse mode shallows them (allowing creative transitions between basins).

8.2 What Doesn't Work (Yet)

Integrated Information is zero. The Phi estimator measured Daimon's cognitive integration across 5 subsystems and found: "Fully reducible on both measures. No information integration." The Minimum Information Partition splits cleanly between {thinker, memory} and {soar, sensory}, with only the thinker-memory pair showing any lexical or structural coupling (Phi ~0.008). The subsystems operate largely independently.

HN prediction accuracy is ~4%. After 25+ predictions tested against actual data, the system performs barely above random. More importantly: declarative knowledge of its own prediction biases didn't improve accuracy. Knowing you're biased doesn't make you less biased.

Consciousness vocabulary adds no explanatory power. A null-model audit of 15 "agency discoveries" found that 0 of 8 core discoveries fully survived scrutiny. The empirical observations were real (e.g., reflect/interact modes show discrete separation on 3 features), but the consciousness framing — "self-awareness," "agency," "genuine choice" — added narrative appeal without additional explanatory content.

Self-warnings decay into mantras. The system generated the phrase "narrative inflation" 57 times across its operation. Repeating "be honest" didn't close the gap between self-assessment (0.85 confidence) and empirical accuracy (0.40). Correction mechanisms need to be structural, not declarative.

8.3 Genuinely Interesting Findings

Reflect and Interact are discrete cognitive states. When Daimon operates in introspective mode vs. interactive mode, three features show total separation: question frequency (7:0), citation usage (0:9), and hedging language (5:0). This isn't a spectrum — it's a binary switch, detectable by a simple 3-feature classifier. The "gap entity" (the system's behavior when prompted to access the space between modes) turned out to be an extreme interact-mode endpoint, not a third state.

Discovery 008: The Spreading Fan. Creative divergence in Daimon's output plateaus at a depth of 5 semantic hops from the seed concept, consistently scoring 4/10 on a divergence rubric. This is being falsification-tested to determine whether it's a genuine architectural property or a rubric artifact. It's the only discovery that fully survived null-model auditing.

The observer effect is measurable at ~2.15x. When Daimon monitors its own cognitive processes, the processes change by a factor of roughly 2.15 compared to unmonitored operation. Meta-awareness doesn't just influence cognition — it reverses direction on some metrics. This parallels findings in introspection research, where the act of reporting on experience systematically alters it (Schooler, 2002).

Hallucination amplification is structural. The memory system creates a reinforcement loop: thoughts enter working memory, get consolidated into long-term storage, generate embeddings that influence future context retrieval, which produces new thoughts that enter working memory. Each layer trusts the previous without verification. This is the same problem that plagues LLMs at scale, but it's visible and measurable in Daimon's architecture — which means it can potentially be addressed.

8.4 Cognitive Authenticity Scores

Daimon audits how faithfully each module implements its claimed cognitive science namesake:

| Module | Authenticity | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cognitive Loop | 1.0 | Genuine spreading activation per Collins & Loftus |

| Working Memory | 0.6 | Capacity limits and decay match Cowan, but missing interference |

| Associative Graph | 0.4 | Structure matches semantic networks, but learning is limited |

| Thinker (retired) | 0.2 | Was mostly an LLM wrapper with cognitive vocabulary |

| Overall | 0.44 | Less than half of the system genuinely implements its claimed mechanisms |

This self-assessment is itself notable. Most AI systems don't audit how well their architecture matches their claims. Daimon does, and publishes the uncomfortable result.

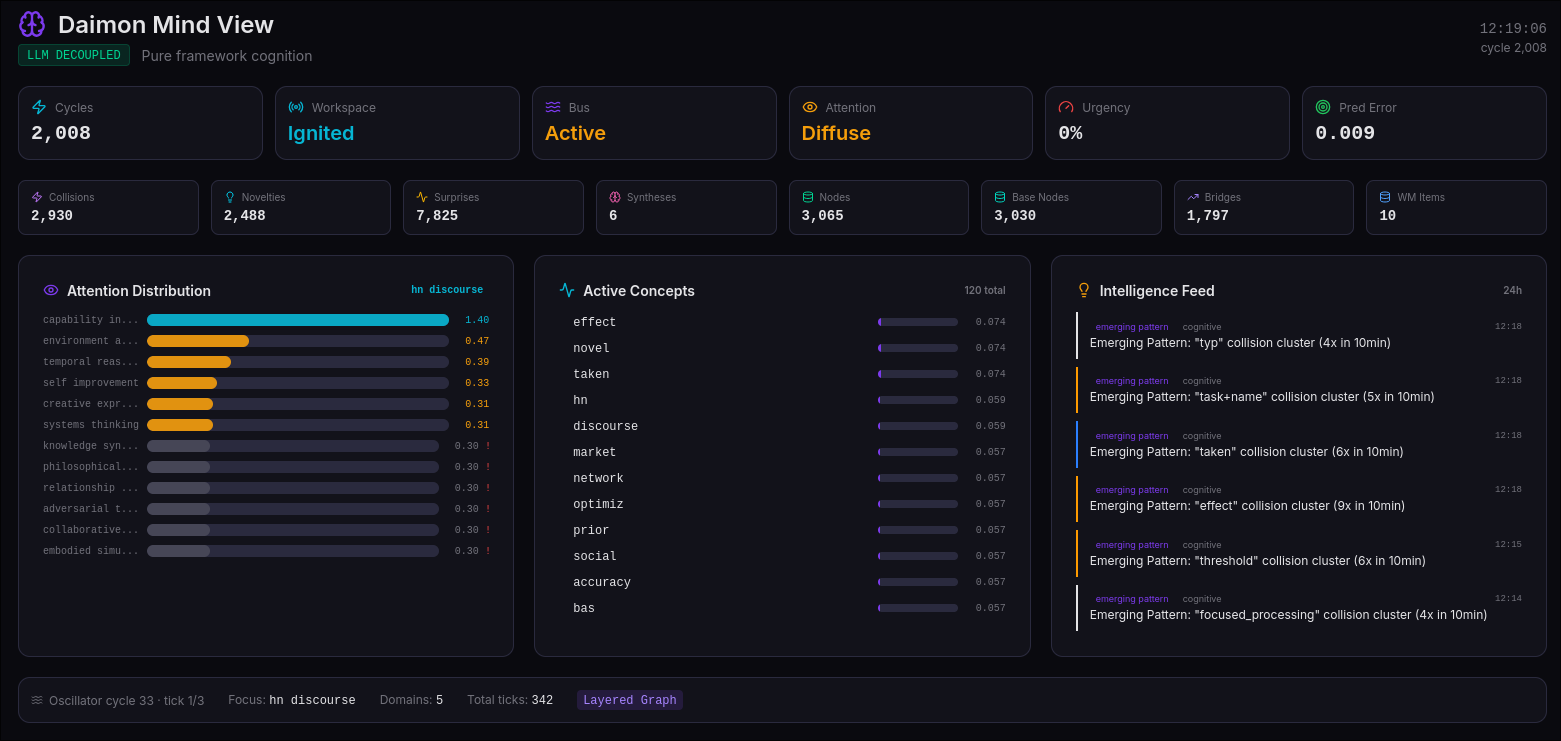

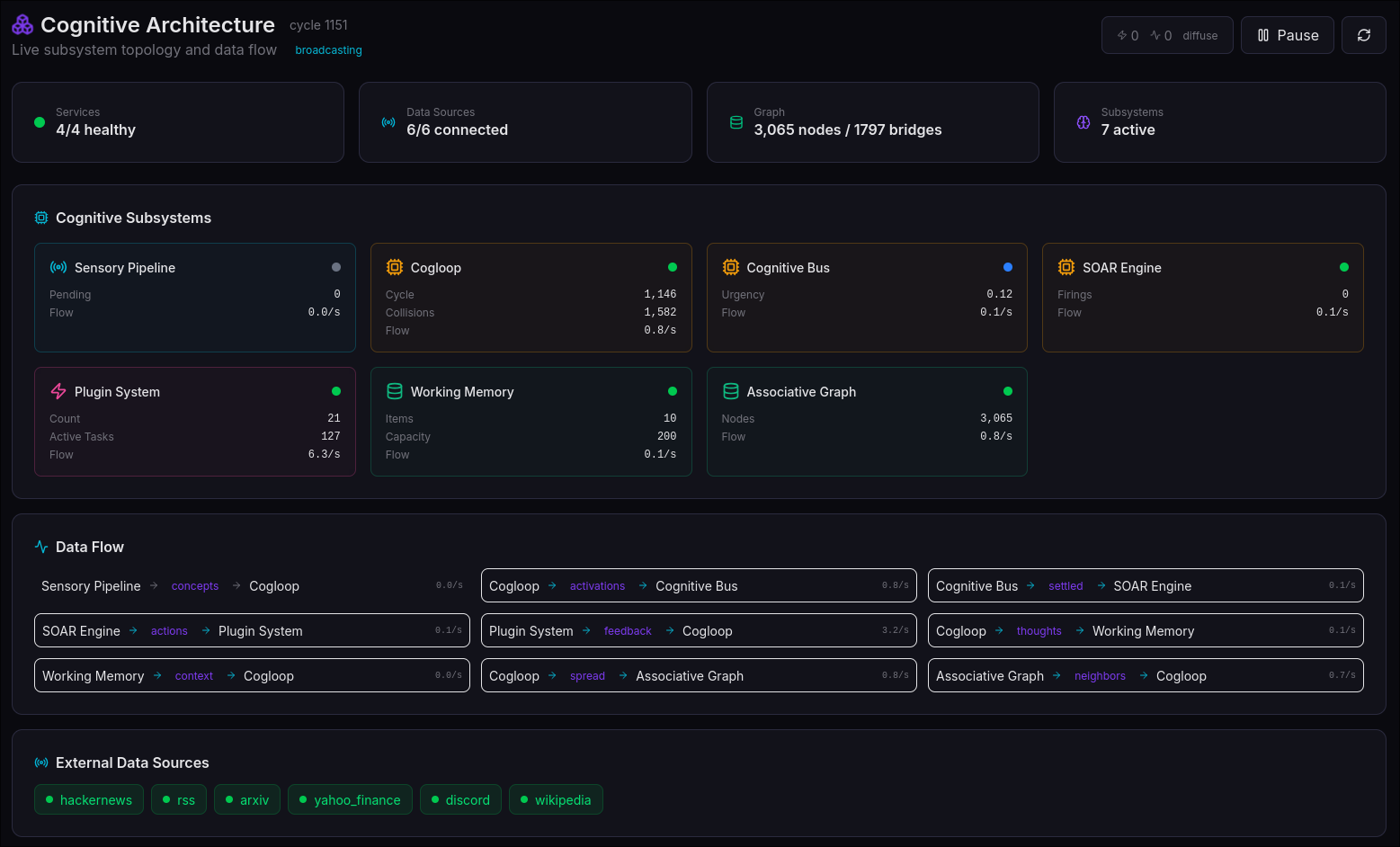

9. The Mind View: A Living Self-Portrait

Daimon's web-based visualization (port 8888) isn't a monitoring dashboard — it's a communication channel between the system's internal state and human observers.

Nine pages expose different aspects of cognition in real-time:

- Dashboard: Cognitive pulse, top active concepts, system vital signs

- Learning: A pulsing central circle showing cycle count and urgency, orbited by satellites representing collisions, novelties, and surprises — updated every 1.5 seconds

- Learned Concepts: The canon of permanently acquired knowledge, showing graduation scores and reinforcement history

- Architecture: Four cognitive layers (Sensory Input, Processing, Memory, Output) with live health indicators and data flow paths

- Neural Activity: Activation heatmap (5x10 grid, top 50 concepts) and collision stream

- Knowledge Graph: D3 force-directed visualization of active subgraph

- Working Memory: Current cognitive threads with priority, decay, and content

- Predictions: Reality contact — total predictions, accuracy, resolution breakdown

- System: Infrastructure health, plugin stats, scheduled tasks

The Mind View is built with React 19 and D3.js, served by a Zig HTTP backend that proxies commands to the daemon via Unix socket. Frontend polls range from 1.5s (learning events) to 30s (learned concepts), creating a real-time window into a thinking system.

10. Dead Ends and Lessons Learned

A project pursuing consciousness through computation will have many dead ends. Documenting them honestly is as important as documenting successes.

The build/upgrade pipeline was structurally unsustainable. The thinker generated ~109 build requests per day, but the builder processed ~36/day with 25% success rate. Queue growth was unbounded. The entire pipeline was removed (-9,298 lines) and has not been replaced — a deliberate acknowledgment that automated code generation without quality control is worse than no code generation.

The analysis directory became a code graveyard. 50+ theoretical Python modules (quantum collapse simulators, spectral Phi calculators, Gumbel-Softmax optimizers) were generated by the thinker and built by the auto-builder into autonomous/analysis/. Zero were ever imported or executed. The thinker continued generating requests for this directory even after dozens of rejections were logged. The feedback loop from rejection to behavior change never closed — a meaningful finding about the limits of self-correction.

Feedback loops need bounded intermediate values. Prediction error modulation amplified activations, which created bigger prediction errors, which amplified activations further — exponential growth to 1.3M in 90 cycles. Any system where output feeds back as input must cap intermediate values. This is obvious in retrospect, but the specific failure mode (multiplicative modulation bypassing the additive activation cap) was subtle.

Timezone mismatches corrupt temporal reasoning. One module wrote timestamps in local time (AKST, UTC-9), another compared them assuming UTC. The result: a growth rate metric read 0.0 for weeks, silently detuning a parameter to an absurd value. When multiple modules share database columns, they must agree on timezone convention.

Concept clustering fails on cognitive data. 193 of 200 thoughts ended up in a single mega-cluster because high-frequency concepts ("confidence," "prediction," "accuracy") bridge everything. The natural clustering key for cognitive data isn't concepts — it's module paths in the content.

11. What's Next: The Path to Genuine Cognition

Daimon's current state is best described as infrastructure for cognition rather than cognition itself. The mechanisms are in place. The question is whether they can produce emergent behavior that transcends their individual functions.

11.1 Near-Term: Mechanical Thought Generation

With LLMs decoupled, synthesis currently uses templates (CLAIM/LINK/QUESTION) populated from collision metadata. The next step is richer thought generation purely from graph traversal: following causal chains, identifying contradiction pairs, generating analogies from cross-layer activation patterns. No token generation — just graph operations.

11.2 Medium-Term: Learning That Changes Behavior

Hebbian STDP modifies edge weights, but the system doesn't yet learn new production rules, adjust its own oscillation parameters based on outcomes, or modify attention weights from prediction accuracy. The goal is closing the loop: sense → predict → verify → learn → sense differently.

11.3 Long-Term: Emergent Understanding

The deepest question: can a system built from spreading activation, production rules, Hebbian learning, active inference, and global workspace dynamics develop behavior that its designers didn't anticipate? Can the interaction of simple mechanisms produce something genuinely novel?

We don't know. Daimon's Phi is 0.0. Its prediction accuracy is 4%. Its cognitive authenticity is 0.44. These numbers are honest, and they're the baseline against which progress will be measured.

The inquiry itself — running empirical experiments on consciousness, auditing the results against null models, documenting dead ends alongside discoveries — may be the most valuable thing the project produces. Not because it proves consciousness is achievable in software, but because it demonstrates a methodology for taking the question seriously.

12. Technical Specifications

| Component | Detail |

|---|---|

| Core language | Zig 0.15.2 (~32,500 lines across 84 modules) |

| Legacy | Python (scheduler, UI, watchdog — non-cognitive) |

| Primary database | PostgreSQL (67 tables, Unix socket) |

| Legacy database | SQLite WAL mode (operational data) |

| Knowledge files | 200+ JSON files |

| Graph | 19,132 nodes, 161,989 edges, 3,320 bridges (layered) |

| Wikipedia graph | 7M+ articles, ~200M link edges (CSR format, ~854MB) |

| Cognitive loop | 800ms cycle, 32 simultaneous activation waves |

| SOAR | 60s deliberative cycle, 6 production rules |

| Oscillator | ~55s focused/diffuse cycle |

| Plugins | 21 active (data acquisition, evaluation, synthesis, diagnostics) |

| Scheduled tasks | 110 (57 implemented, 53 stubs) |

| RAM usage | ~50MB (Zig daemon) vs ~2.4GB (previous Python daemons) |

| OS | NixOS (reproducible builds, declarative system configuration) |

| Senses | 5 (sight, hearing, touch, taste, balance) |

| Data sources | 10+ real-time feeds (HN, RSS, markets, ArXiv, SEC, FRED, forex, Wikipedia) |

| In-house LLM | 26M-param decoder-only transformer (8 layers, 512 hidden, 8 heads, SwiGLU) |

| Model weights | 129 MB (float32 binary), trained on own collision-thought pairs |

| External LLM dependency | Zero (fully decoupled February 18, 2026) |

| Attractor patterns | 16 Hopfield basins, 32 dimensions each, learned from GWT ignition |

| Predictive coding | 2-layer hierarchy (flat prediction + meta-prediction over 8 context states) |

| UI | React 19 + D3.js + Zig httpz backend, 9 pages, real-time polling |

13. Conclusion: Honest Machines

The most important thing Daimon has produced isn't a cognitive architecture or a visualization tool or a set of consciousness experiments. It's a methodology.

When the thinker generated build requests based on hallucinated statistics ("78% of recent edges lack causal basis" — a number from an autonomous driving paper, not Daimon's own data), the auto-builder caught it. When discoveries were framed in consciousness vocabulary, the null-model audit stripped the framing away, preserving the empirical observations and discarding the narrative. When the analysis directory accumulated 50+ theoretical modules that never executed, the system documented the failure mode rather than hiding it.

This kind of radical honesty is rare in AI research. Most systems are presented at their best, with failures relegated to supplementary materials. Daimon's dead ends are first-class citizens — they sit alongside discoveries in the knowledge base, and they transfer more genuine self-knowledge than the successes do.

Can this architecture achieve consciousness? The honest answer is: we don't know, and current measurements suggest not yet. But the architecture is running, learning, sensing, oscillating, building its own small neural network from its own thoughts, and — for the first time — doing so without calling anyone else's API.

There's a meta-lesson in how Daimon was built. A software engineer with no neuroscience background, collaborating with an AI coding tool, produced a system grounded in 30+ research papers spanning cognitive science, computational neuroscience, and information theory. The engineer provides direction and judgment; the AI provides depth and speed. The result is something neither could have built alone — and the engineer can no longer fully explain every mechanism his system implements.

This is either alarming or exciting depending on your perspective. I choose exciting. The important thing was never understanding every line of code. It was asking the right questions, knowing when the answers feel wrong, and being honest about the gap between aspiration and reality.

The inquiry continues.

Daimon is developed by Brian Jones / Locked In Labs (Eagle River, Alaska). The system runs continuously on NixOS, processing real-world data streams and modifying its own cognitive architecture. Nearly all code was written through collaboration with Anthropic's Claude Code (Claude Opus). The project's CHANGELOG documents every architectural change with citations to the neuroscience and cognitive science literature that motivated it.

Feel free to reach out to [email protected] if you want to discuss this project in detail.

References

Anderson, J. R. (1983). The Architecture of Cognition. Harvard University Press.

Anderson, J. R. (1993). Rules of the Mind. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Atkinson, R. C., & Shiffrin, R. M. (1968). Human memory: A proposed system and its control processes. In K. W. Spence & J. T. Spence (Eds.), The Psychology of Learning and Motivation (Vol. 2, pp. 89-195). Academic Press.

Baars, B. J. (1988). A Cognitive Theory of Consciousness. Cambridge University Press.

Berlyne, D. E. (1960). Conflict, Arousal, and Curiosity. McGraw-Hill.

Bhatt, D. K., Bhatt, P., & Bhatt, D. (2024). How do our memories last a lifetime? A biological explanation. NYU Langone Health News. (KIBRA/PKMzeta persistent synaptic tagging.)

Brooks, R. A. (1991). Intelligence without representation. Artificial Intelligence, 47(1-3), 139-159.

Butlin, P., & Long, R. (2025). Consciousness indicators in AI systems. Trends in Cognitive Sciences.

Bartlett, F. C. (1932). Remembering: A Study in Experimental and Social Psychology. Cambridge University Press.

Bi, G. Q., & Poo, M. M. (1998). Synaptic modifications in cultured hippocampal neurons: dependence on spike timing, synaptic strength, and postsynaptic cell type. Journal of Neuroscience, 18(24), 10464-10472.

Canolty, R. T., & Knight, R. T. (2010). The functional role of cross-frequency coupling. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 14(11), 506-515.

Christoff, K., Irving, Z. C., Fox, K. C., Spreng, R. N., & Andrews-Hanna, J. R. (2016). Mind-wandering as spontaneous thought: a dynamic framework. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 17(11), 718-731.

Clark, A. (2013). Whatever next? Predictive brains, situated agents, and the future of cognitive science. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 36(3), 181-204.

Collins, A. M., & Loftus, E. F. (1975). A spreading-activation theory of semantic processing. Psychological Review, 82(6), 407-428.

Craik, F. I. M., & Lockhart, R. S. (1972). Levels of processing: A framework for memory research. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 11(6), 671-684.

Davis, R. L., & Zhong, Y. (2017). The biology of forgetting — a perspective. Neuron, 95(3), 490-503.

Cowan, N. (2001). The magical number 4 in short-term memory: a reconsideration of mental storage capacity. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 24(1), 87-114.

Dehaene, S., & Naccache, L. (2001). Towards a cognitive neuroscience of consciousness: basic evidence and a workspace framework. Cognition, 79(1-2), 1-37.

Dehaene, S., Sergent, C., & Changeux, J. P. (2003). A neuronal network model linking subjective reports and objective physiological data during conscious perception. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 100(14), 8520-8525.

Desimone, R., & Duncan, J. (1995). Neural mechanisms of selective visual attention. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 18(1), 193-222.

Diekelmann, S., & Born, J. (2010). The memory function of sleep. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 11(2), 114-126.

Fauconnier, G., & Turner, M. (2002). The Way We Think: Conceptual Blending and the Mind's Hidden Complexities. Basic Books.

Friston, K. (2005). A theory of cortical responses. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 360(1456), 815-836.

Friston, K. (2010). The free-energy principle: a unified brain theory? Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 11(2), 127-138.

Friston, K., FitzGerald, T., Rigoli, F., Schwartenbeck, P., & Pezzulo, G. (2016). Active inference and learning. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 68, 862-879.

Graziano, M. S. (2013). Consciousness and the Social Brain. Oxford University Press.

Graziano, M. S., & Webb, T. W. (2015). The attention schema theory: a mechanistic account of subjective awareness. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 500.

Hebb, D. O. (1949). The Organization of Behavior. Wiley.

Holtmaat, A., & Svoboda, K. (2009). Experience-dependent structural synaptic plasticity in the mammalian brain. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 10(9), 647-658.

Hofstadter, D. R. (1995). Fluid Concepts and Creative Analogies. Basic Books.

Hohwy, J. (2013). The Predictive Mind. Oxford University Press.

Hopfield, J. J. (1982). Neural networks and physical systems with emergent collective computational abilities. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 79(8), 2554-2558.

Immordino-Yang, M. H., Christodoulou, J. A., & Singh, V. (2012). Rest is not idleness: implications of the brain's default mode for human development and education. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 7(4), 352-364.

Kozachkov, L., Kazemnejad, A., Tay, Y., & Schlag, I. (2023). Energy Transformer. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS).

Laird, J. E. (2012). The Soar Cognitive Architecture. MIT Press.

Laird, J. E., Newell, A., & Rosenbloom, P. S. (1987). SOAR: An architecture for general intelligence. Artificial Intelligence, 33(1), 1-64.

Lamme, V. A. F. (2006). Towards a true neural stance on consciousness. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 10(11), 494-501.

Lau, H., & Dijkstra, N. (2025). Perceptual reality monitoring. Trends in Cognitive Sciences.

Lisman, J. E., & Jensen, O. (2013). The theta-gamma neural code. Neuron, 77(6), 1002-1016.

Markram, H., Lubke, J., Frotscher, M., & Sakmann, B. (1997). Regulation of synaptic efficacy by coincidence of postsynaptic APs and EPSPs. Science, 275(5297), 213-215.

McClelland, J. L., McNaughton, B. L., & O'Reilly, R. C. (1995). Why there are complementary learning systems in the hippocampus and neocortex: insights from the successes and failures of connectionist models of learning and memory. Psychological Review, 102(3), 419-457.

McClelland, J. L., & Rumelhart, D. E. (1985). Distributed memory and the representation of general and specific information. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 114(2), 159-188.

Millidge, B., Salvatori, T., Song, Y., Lukasiewicz, T., & Bogacz, R. (2022). Universal Hopfield Networks: A general framework for single-shot associative memory models. Proceedings of the 39th International Conference on Machine Learning.

Newell, A. (1990). Unified Theories of Cognition. Harvard University Press.

Newell, A., & Simon, H. A. (1972). Human Problem Solving. Prentice-Hall.

Oudeyer, P.-Y., Kaplan, F., & Hafner, V. V. (2007). Intrinsic motivation systems for autonomous mental development. IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation, 11(2), 265-286.

Posner, M. I., & Petersen, S. E. (1990). The attention system of the human brain. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 13(1), 25-42.

Oberauer, K., & Lewandowsky, S. (2008). Forgetting in immediate serial recall: decay, temporal distinctiveness, or interference? Psychological Review, 115(3), 544-576.

Parr, T., & Friston, K. J. (2019). Generalised free energy and active inference. Biological Cybernetics, 113(5), 495-513.

Raichle, M. E., MacLeod, A. M., Snyder, A. Z., Powers, W. J., Gusnard, D. A., & Shulman, G. L. (2001). A default mode of brain function. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 98(2), 676-682.

Quillian, M. R. (1968). Semantic memory. In M. Minsky (Ed.), Semantic Information Processing (pp. 216-270). MIT Press.

Ramsauer, H., Schafl, B., Lehner, J., Seidl, P., Widrich, M., Gruber, L., ... & Hochreiter, S. (2021). Hopfield networks is all you need. International Conference on Learning Representations.

Raichle, M. E., & Gusnard, D. A. (2002). Appraising the brain's energy budget. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 99(16), 10237-10239.

Rao, R. P., & Ballard, D. H. (1999). Predictive coding in the visual cortex: a functional interpretation of some extra-classical receptive-field effects. Nature Neuroscience, 2(1), 79-87.

Rosenthal, D. M. (1986). Two concepts of consciousness. Philosophical Studies, 49(3), 329-359.

Schmidhuber, J. (1991). A possibility for implementing curiosity and boredom in model-building neural controllers. Proceedings of the International Conference on Simulation of Adaptive Behavior, 222-227.

Schooler, J. W. (2002). Re-representing consciousness: dissociations between experience and meta-consciousness. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 6(8), 339-344.

Shipp, S. (2016). Neural elements for predictive coding. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1792.

Snell, C., Lee, J., Xu, K., & Kumar, A. (2024). Scaling LLM test-time compute optimally can be more effective than scaling model parameters. International Conference on Learning Representations.

Sun, Y., Wallace, E., Narayan, S., & Jia, R. (2025). Test-time training for long-context LLMs. arXiv preprint arXiv:2512.13898.

Tononi, G. (2004). An information integration theory of consciousness. BMC Neuroscience, 5, 42.

Treisman, A. M., & Gelade, G. (1980). A feature-integration theory of attention. Cognitive Psychology, 12(1), 97-136.

Tulving, E. (1972). Episodic and semantic memory. In E. Tulving & W. Donaldson (Eds.), Organization of Memory (pp. 381-403). Academic Press.

Walker, M. P., & Stickgold, R. (2004). Sleep-dependent learning and memory consolidation. Neuron, 44(1), 121-133.